🌱 The nature financing gap

At COP30 in Belém, Brazil unveiled the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) — a new international instrument designed to strengthen the protection of tropical and subtropical forests. Supported by governments and private investors, the scheme rewards policies and projects that conserve and restore these ecosystems, recognising the stewardship of those who manage and sustainably use forests. Leveraging the UN Conference’s visibility, the programme has reignited crucial discussions about a key theme in sustainability: closing the nature financing gap.

This urgency is reflected in the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which identifies an annual shortfall of $700 billion in resources needed to improve and restore nature. To achieve its goal of reversing biodiversity loss by 2030, the GBF expects governments to repurpose $500 billion in harmful subsidies. However, a $200 billion gap remains to be mobilised from all sources. While the public sector plays a significant role in this process, private finance must also be leveraged.

The current impact of private finance is one of the main reasons why it needs to be improved. According to the UN’s Environment Programme (UNEP), $5 trillion per year of private finance flows are harmful to nature – a figure 140 times higher than current private sector investment in nature-based solutions.

Shifting this finance offers multiple gains that extend beyond the purely financial returns considered in traditional investments. Restoring and sustainably managing ecosystems can reduce costs and risks from environmental degradation, strengthen its direct and indirect benefits (e.g. pollination), create new business opportunities and jobs in greener sectors, and protect nature’s intrinsic value.

🧾 The regulatory landscape: SFRD and the push for sustainable capital

To transpose this ambition into action, UNEP recommends a key set of actions by the private sector, to be simultaneously complimented by the public sector:

| Private sector | Public sector – to enable nature finance for private action |

| Redirect investments to climate and nature-positive alternatives | Encourage and consider mandating assessment, reporting and disclosure of nature risks, impacts, dependencies and opportunities by business and finance |

| Assess, report and disclose nature risks, impacts, dependencies and opportunities using disclosure frameworks, e.g. Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures | Increase the use of regulation and incentive mechanisms to shape private sector action and behaviour |

| Commit to climate and biodiversity targets, based on tools such as the Science Based Targets Network |

In Europe, pioneering efforts have been established in this field, such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). In force since March 2021, SFDR was developed to reorient investments towards more sustainable alternatives, better manage sustainability risks, and foster transparency in the financial sector.

The Regulation establishes three fund classifications:

- Article 6 funds have no sustainability considerations in their investment strategies.

- Article 8 funds (“light green”) promote some ESG characteristics.

- Article 9 funds (“dark green”) pursue sustainability objectives and aim to achieve a positive impact on the environment and/or society.

Overall, data shows strong interest in integrating sustainability into investments. Morningstar reports that Article 8 and 9 funds account for 58.8% of the market, with €6.8 trillion in assets as of Q3 2025. However, Article 6 funds attracted almost double the new capital of Article 8 funds, while nearly €7 billion flowed out of Article 9 funds in the last quarter.

One of the reasons behind this movement is the high risk of greenwashing and greenlighting – which is not limited to SFRD funds but also affects other nature-related investments. Greenwashing involves promoting investments as sustainable without providing verifiable evidence of their impact. Greenlighting, on the other hand, is the process of selectively highlighting a few sustainable investments while ignoring the majority of a portfolio that lacks any sustainability concern.

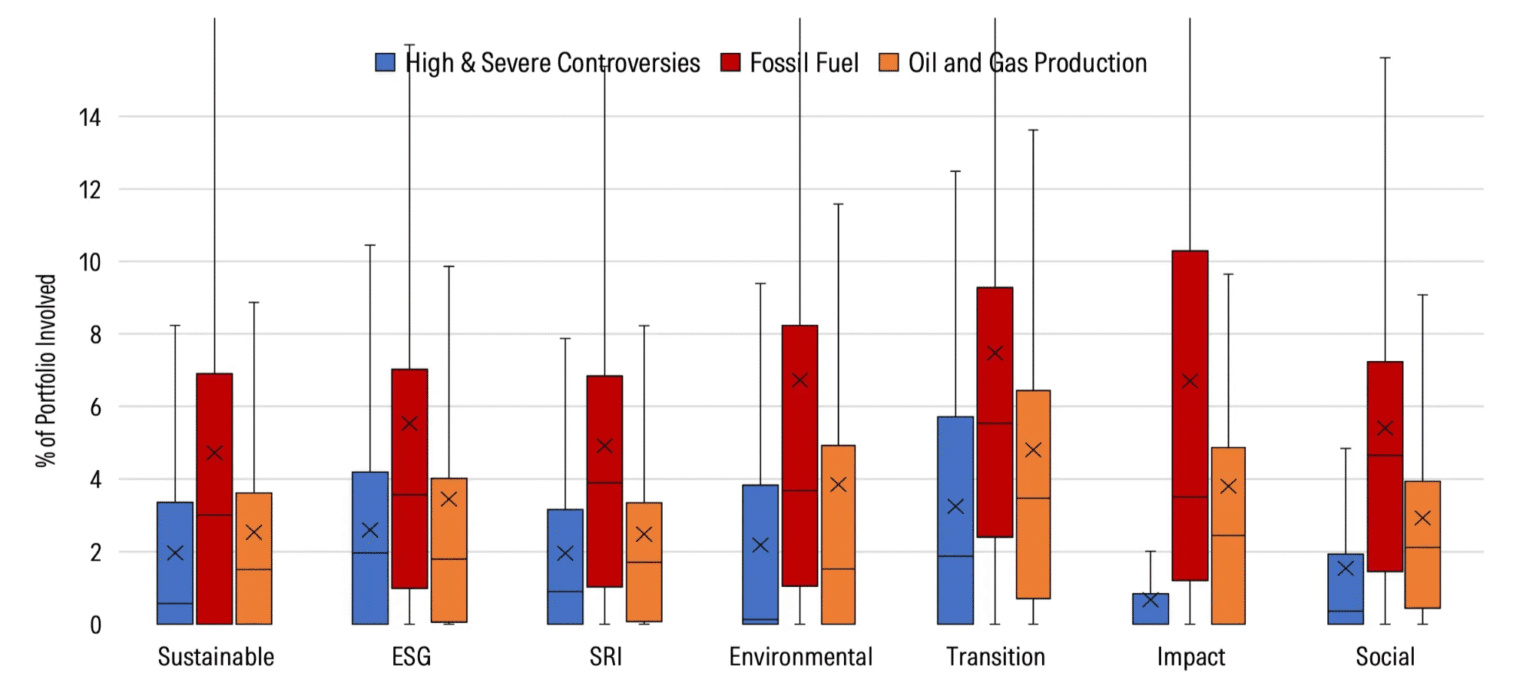

These practices pose serious reputational and financial risks for light and dark green funds. For instance, Morningstar’s analysis has shown that even funds in “Sustainable” and “Environmental” categories were involved in controversial, fossil fuels and oil and gas assets, which have a clear negative impact on the environment and society.

Although SFDR tries to partially mitigate the issue by incorporating principles of Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) and the disclosure of Principal Adverse Impacts (PAIs), they are not generally sufficient to guarantee that Article 8 and 9 funds commit to impactful sustainability goals. Furthermore, beyond these weak anti-greenwashing mechanisms, the existence of overlapping reporting frameworks and conflicting ESG rating methodologies further expands concerns regarding the reliability of these investments.

Yet, it is important to mention that some funds voluntarily assess their sustainability claims through third-party auditing, ensuring more authenticity to their operation. This is the case, for example, of “Objectif biodiversité”, a EUR 150 million fund managed by Starquest and Montefiore Investment – who have chosen Impact Labs to validade its impact on the preservation and restoration of ecosystems.

💥 The path forward: scaling impact

Between regulatory loopholes and greenwashing risks, not to mention the rising anti-climate rhetoric, the scenario for investments in recovering and conserving nature may seem daunting. But there is light at the end of the tunnel.

First, it is clear that policy improvements are needed to better organise the market and incentivise investment in projects and companies with certified impacts. While there is much to be done, the development of mechanisms like the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) demonstrates that some governments are still concerned about this issue and may be willing to further develop these rules.

Second, there is a growing movement for the systematisation of the myriad of frameworks and methodologies that exist in this field. A good example is the newly-issued ISO 17298 standard, which helps organisations understand their impact and dependencies on nature and guides them in including biodiversity into their strategies, operations and decision-making processes.

Third, the SFRD case indicates that funds often lack the capabilities to measure and manage impact effectively. As the the bar for qualifying both financially sound and nature-positive remains high, a strong knowledge foundation is required, with tools and data as the backbone of identifying, tracking and validating environmental impacts.

What organisations need to implement is perhaps complex, but luckily it is known and feasible. And that is exactly what Impact Labs has mastered.

Our expertise supports the improvement of client’s impact data, moving to higher quality sources, and the development of methodologies to assess environmental pressures, including how and when they should be measured. Moreover, our partnership with tools such as Darwin Data allows the quantification of biodiversity impacts and the spatial analysis of how the organisation affects local ecosystems and its proximity to high sensitivity/risk areas.

Conclusions on closing the nature financing gap

At the Impact Labs we believe:

- Impact is the next frontier of investing.

- Impact investing delivers strong long-term value.

- Custom, quantitative impact measurement is key to scaling this transformation.

There is an urgent need to redirect financial flows to protect nature, a systematic change that envolves both the private and the public sector. Although some progress has been made, such as the SFRD, there is still room for improvement. For enterprises, being able to thoroughly assess environmental impact, with the use of data and tools, is a growing need – one that Impact Labs certainly can help with.

References

UNEP Finance Initiative. Governments Adopt First Global Strategy to Finance Biodiversity: Implications for Financial Institutions. UNEP FI.

United Nations Environment Programme. State of Finance for Nature – 2023: Executive Summary. UNEP, 2023.

European Environment Agency. Financing Nature as a Solution. EEA.

Transforming Food Futures Fund. Executive Summary. TFFF, 2025.

The Nature Conservancy. Closing the Nature Finance Gap: Insights from the CBD. TNC.

World Bank. Rules of the Road: Measuring the Impact of Biodiversity Finance. World Bank Blogs.

Carbon Brief. Developed Countries Failing to Pay Fair Share of Nature Finance Ahead of COP16. Carbon Brief.

EY. SFDR Funds: The Power of Voluntary Assurance. EY Insights.

Morningstar. SFDR Article 8 and Article 9 Funds – Q3 2025. Morningstar, 2025.

International Organization for Standardization. ISO 17298. ISO.